I find my way round Warsaw by serendipity and chance mention. So now I’m splashing through puddles and standing far back from zebra crossings on the way to Zachęta gallery. The building is grand, but I don’t take photos outside because I don’t want to kill my camera. But inside, I can’t stop.

I walk up the grand marble staircase, admiring plaster decorations; and wrought iron balustrades; and dragons supporting intricate lampstands. A strange contrast to the folk art I’m there to see. But this is only Paradox 1.

The exhibition is an attempt to answer a number of questions. What was the place of folk lore and folk art in the first decades of the People’s Republic of Poland? How did the people’s government use them? How did the status of folk art change when it began to appear in museums and galleries? How did the folk artist fit into the art world? As I ramble through the exhibits, there’s a game to play: spot the paradoxes.

Once I enter the exhibition space grandeur is replaced by colour and the skill of hands. I’ve met the women folk painters of Zalipie before, in images of their painted village. After the war they were “discovered” and became very popular. They began to work with professional artists in design collectives, creating textile patterns and plate decorations. The flower patterns from cottages and barns were adapted as decorations for ocean liners and used in the Palace of Culture and Science on chandeliers. (Paradox 2)

The double warp textiles from Białystok province were produced to save local tradition: however it was clear that “what you did for the city buyer was different from what you did for yourself”. The display of some of these textiles is fronted by a screen showing images of people dressed in a variety of folk costumes.

Paradox 3 emerges here: government funding for ethnographic research runs parallel to changes in the countryside, such as collectivisation, that were busy wiping out folk culture. In the 1950s and 1960s there were folk-themed field trips for designers from the Institute of Industrial Design which led to design collectives combining “the expertise and skill of fine artists with the unbridled imagination, fresh ingenuity and prolificacy of informal groups.” Field research resulted in collections for museums, catalogues and atlases, including one of Polish folk costumes assembled by Tadeusz Seweryn. Folk art moves out of the countryside.

In 1965, many years of research conducted by the Studio of Non-Professional Art Research at the Polish Academy of Sciences institute of Art culminated in an exhibition called “Others”. The most spectacular part was the sculpture section, reconstructed here in the second room. The figures are mainly wooden, polychromed or oiled: a woman with four birds; a pensive Christ; a girl with a deer; a man with an accordion; a deer; a crocodile; a whale; and the wonderfully titled “The devil, death and a messenger”. I am preoccupied, moving round the display, looking for a way to photograph each item separately, when I feel an agitated tap on my shoulder. The attendant is shaking his head and pointing to a “no cameras” sign – a ban in place for just these two tables. I’m not noble enough to sacrifice the stolen image of the woman: the cupboard-full I am free to photograph.

The third room is spacious, two tables displaying ceramic jugs beautifully free of glass cases. Antoni Kenar, a teacher at the High School of Fine Arts in Zakopane, crafted these in 1948-49, drawing on folk, children’s and prehistoric influences to achieve “the rawness of the primitive.” The rest of the space in the room is filled with sound, improvised music inspired by the traditional music of the Radom area played on instruments including the violin, basolin and hand drum.

The exhibits move away from individual objects to focus on buildings. As part of the government’s six year plan, Nowa Huta was built near Kraków as self-sufficient housing for workers, a symbol of transformation. In that city now, the Cepelia store retains the original 1950s interior, complete with hand-painted ceramic tiles on the ceiling like these, representing soviet-era Polish design drawing on folk art. A far cry from the pomposity and grandiloquence of the Palace of Science and Culture, and Paradox 4.

In 1959, the determination “Peasants will have a house in Warsaw” led to the building of Dom Chopła, a hotel and cultural centre to cater for organised groups visiting from the country. Modernist inside and out, it contained a library, a common room and a combined cinema / theatre. It is now the Hotel Gromada. As an erstwhile Australian peasant, I’m contemplating spending a night there.

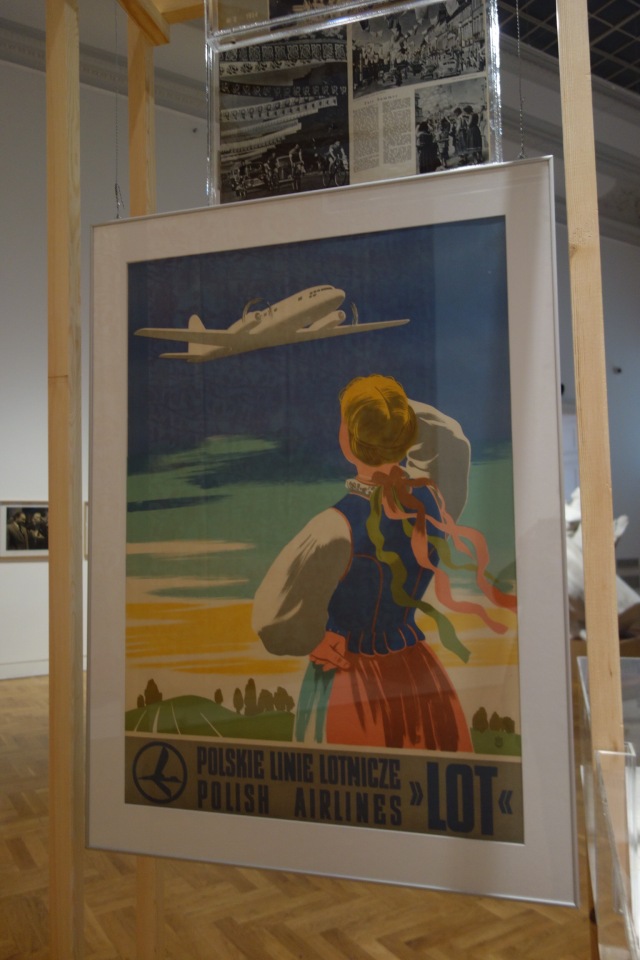

The final room contains 3 big screens showing dancing and processions; posters using folk-art imagery with a camera ban for most of them; and a number of sculptures. The chunkiness of the dancers is social realism in style, but somehow other elements intrude: athleticism, grace, even something mildly bawdy – from the other side the women’s breasts are dominant, and the man’s hat suggests maybe the decadence of the jazz age. Paradox 6?

Paradox 6 comes in the form of the 1953-5 plaster models for a sculpture group called Regions of Poland by Franciszek Masiak. Intended for the state council building, it shows pairings of people who are really listening to each other in a way I find both intimate and touching – not at all as I conceive of discourse under communism.

The final information panel sums up the overall paradox of folk art under communism: folk traditions were equated with superstition and anachronism, and yet in an economy geared to industrialisation folklore was politically and economically exploited. The peasants were meant to feed the city and also entertain it: the annual Cepeliada festivals organised by – wait for it – Folk Industry Central, combined modernism and folksiness. The intelligentsia saw the countryside as “exotic”and sought its products, in much the same way hipsters now frequent the soviet era, still government-subsidised, milk bars.

The advertisement for the Polish airline encapsulates the paradoxes that have been apparent throughout the exhibition – technology and folk linked in paradox.

It’s time to leave the exhibition and my encounters with yet another side of communist Poland. I take the paradoxes and my ambivalences with me, as I go down the grand staircase towards the grand front door (which opens automatically.)

But first I have to retrieve my coat from the cloak room. As I descend, I’m surrounded by disconcerting mirrors and have to watch my footing on the marble stairs very carefully. Halfway down I’m deluged in red light and neon, and a perspective stretching through arches, leading who knows where. When I stop to photograph, I realise it will invitably be a multiplication of selfies.

I step outside into afternoon rain, and walk through Saxon Garden puddles, under autumn trees, to the tram.

Fascinating…..and stunning

LikeLike

What a cornucopia of wonders, Meg! I was in love with the grandeur and twirly dragons before we even got started 🙂 You knew I would be. The wall of plates tugs at my heart strings. I have a Delft rack displaying mine at home. And that embroidery work is exquisite. I would say more but I’m off out for a woodland walk with the group. First since Dad so explaining will be called for. See you soon hugs 🙂 🙂

LikeLike

Here the buildings are half the art often. At home too, on a much humbler scale – an old church and an old post office (at least old by our standards.) and the Australian museum in Canberra is new-spectacular. I’m glad the dragons tickled your fancy. I thought the information whatsamijigs were pretty good this time.

Does it qualify as a walk?? You can have it if you like.

LikeLike

That would be rather nice. 🙂 It would be one of my more informative contributions. Heard anything from Gilly? I’ve texted but I don’t like to pester. Will respond to your email later.

LikeLike

It hardly qualifies as a walk! Except through an aspect of a period. No word from Gilly. I too am hesitant to contact her again. Only answer my email if you really want to, and have the time. Hugs heading your way via yellow sudmarine.

LikeLike

I’m sorry I didn’t keep in touch as much as I’d have liked to, the number of calls and messages etc were amazing, but I couldn’t find the energy or concentration. I’m feeling okay now, just get tired too quickly, today I walked a mile, bit slow but didn’t collapse in a heap afterwards! I’ll know more on Tuesday x:-)x

LikeLike

I didn’t want to add to your troubles, honeybun. Just anxious for you. Gentle hugs 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ahh you’re adorable, wish you lived down here!

LikeLike

Me too 🙂

LikeLike

Love all these examples of folk art Meg. I have to say that I was after that kind of thing at Manufaktura in Prague, but was disappointed to find very little there. Your comment about the difference between what was made for city people and for the makers themselves said a lot about authenticity, or the lack of it, and market-driven artistic styles everywhere. Aboriginal art in Australia is a case in point. But artists have to eat!

LikeLike

Difference maybe between a shop and a museum. It wasn’t actually my comment about different makings: it was something the makers themselves said. I suspect the folk artists may have been eating quite well before all the interference with farms, and disruption to a way of life. Point well made about Aboriginal art.

LikeLike

Love that folk art, what a great visit! I did laugh at the selfies – not your sort of thing!

LikeLike

How else would I get that hellish neon red? Besides, reflected selfies smoothe away the wrinkles.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, there’s always a positive side to things!

LikeLike

Always a delight to walk with you, even into the depths of hell by the looks of it! Though I did like the wrinkle-free selfies 😀

LikeLike

What a wonderful place to visit on so many levels, Meg. You always find the best things to explore! I love the intricacies of the wrought ironwork in the building – absolutely gorgeous! And I always find folk art interesting, especially things created by people who otherwise may have seemed ordinary, and art that otherwise had a functional purpose. I also really like the plaster models for the sculptures. There’s something simple yet so strong about the lines in each piece. The fact that each pair of people is facing each other does suggest intimacy in an unexpected way, like you’ve said. Thanks for taking us with you on your tour!

LikeLike

Pingback: Jo’s Monday walk : Rocha Delicada | restlessjo

I do like those jugs, all of them! The bird tiles and the intimate conversation couples are splendid, but best of all the lovely lady surrounded in a glowing red!

LikeLike

Pingback: Another part of the city | 12monthsinwarsaw